Maqam is a word that brings up ideas in our head immediately.

Over the last century or more we have generally discussed maqams in terms of scales, intervals, jins/ajnas (trichords, tetrachords, and pentachords), sayir/seyir (melodic pathway/movement).

But did you know that there was a time that nobody in the middle east discussed music with the word “maqam”. This word was not a musical term until the 15h century.

So where did the word “maqam” come from?

The word maqam means, “place”, “location”, “seat”, in Arabic. But what does this meaning have to do with music? Here’s some background.

Since the middle east started to use the solfege system, and staff notation, we lost something of the origins of maqam.

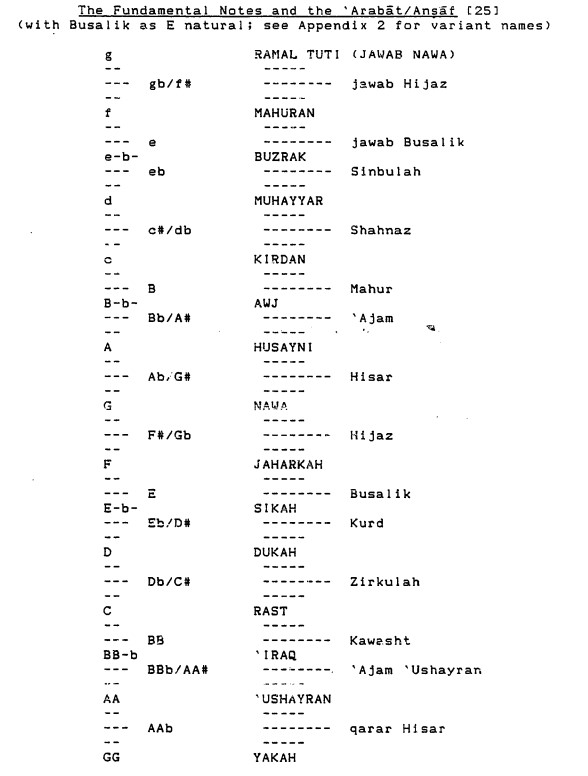

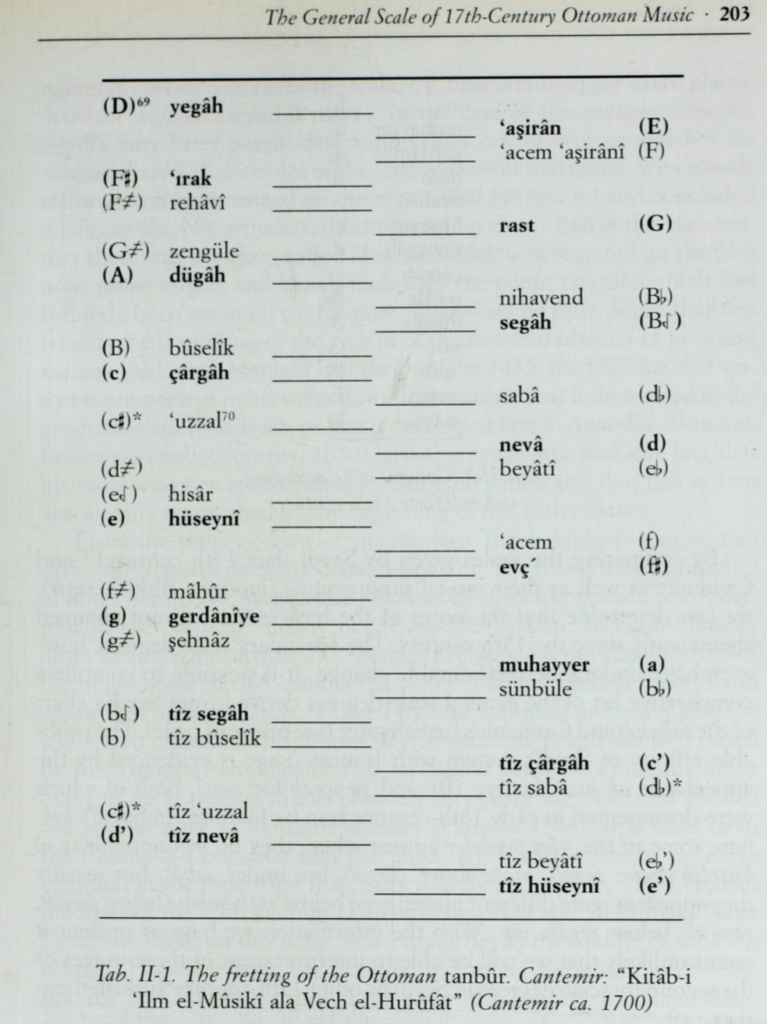

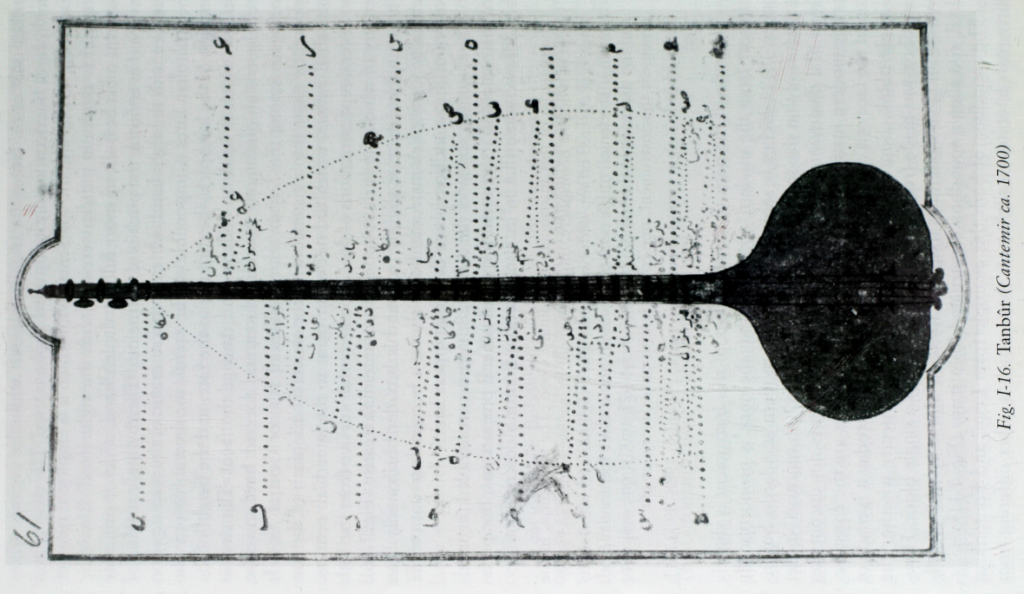

Before we started using solfege, we used a system of modal names to make reference to notes on the fingerboard of an instrument.

You’ll notice that you see note names that correspond to maqams like Rast, Huseyni, Nihavend, etc.

Why use the word “maqam”? Because it indicates a location, place, or seat on the fingerboard.

Walter Feldman shows evidence that was a logic to the naming and placing of names to the maqams.

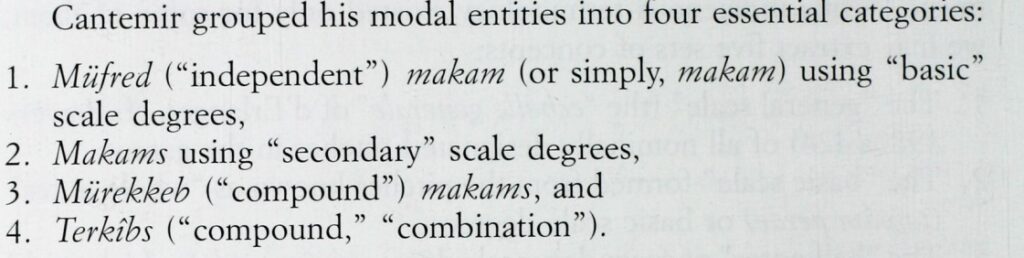

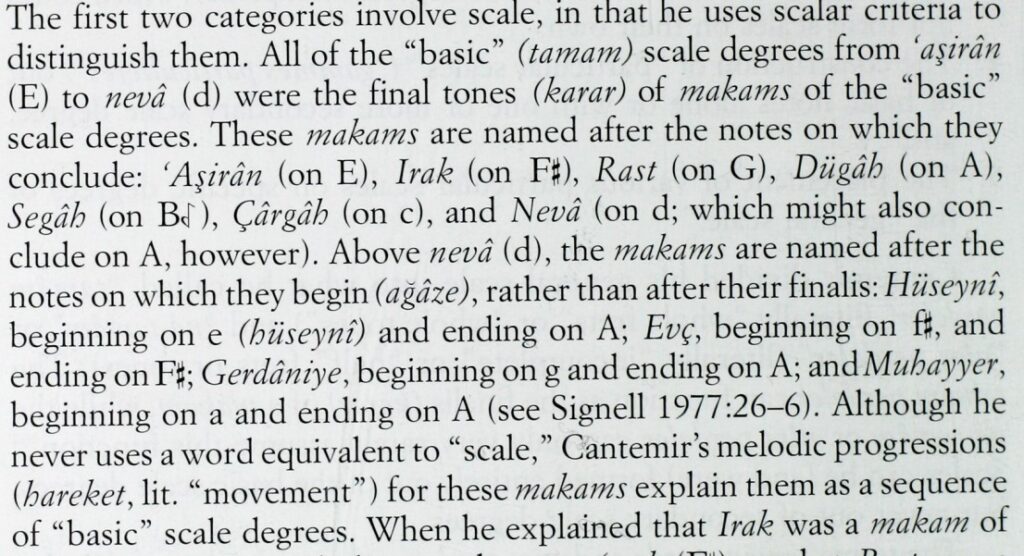

He writes about the work of Cantemir, a Moldavian Prince who came in service of the Ottoman court in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Cantemir differentiated between different modal structures to which we presently all call “maqam”.

The note names that are bolded in the above images are the notes of the basic scale which also correspond to why the term maqam is used, because it refers to a “location” on the fretboard, the “seat” of a note on the fretboard.

Feldman continues, “The identity of makam and note names proves that the particular scales (makams, avazes, shu’bas and terkibs) were positioned upon particular degrees of the general scale.”

Feldman also indicates that, “The texts of the Systematist tradition, whether written in Arabic of Persian do not mention this system, and do not indicate where the pardas (primary modes) and (sho’bas (secondary modes) were placed. Abdulkadir Maraghi (d. 1435) still employed the older Perso-Arabic system of letter combinations to indicate the notes of the general scale and of the various particular scales without linking these notes to the names of the modal entities.”

So, pre-15th century musicians and theorists were using the terms “parda” (which can be translated as mode or fret), and “sho’ba” to indicate primary and secondary modes.

Even later in the 18th century another writer on music Abdulbaki Dede used “the term makam only for the seven modes based on the lower notes of the fundemental scale (makams ‘Irak, Rast, ‘Ussak-Dugah, Segah, Cargah, Neva, Huseyni) plus Muhayyer, the descending version of Huseyni. Everything else is classed by him as terkib” according to Walter Feldman. (Terkib means combination, or compound)

You could argue that this is all semantics, however, it is a very enlightening tool to have to describe the modes.

Feldman argues that at some point among the Turkic peoples of Central Asia or Anatolia, musicians started to name the locations of notes on the fretboard of long-necked lutes according to modal identities that were identifiable by their location (maqam) on the fretboard.

Hence, this is how the word maqam came to be used to refer to modes.

Seyir/Sayir

The word seyir/sayir means pathway, or course. I have seen many complicated ways of describing seyir. I used to think that seyir was best described using jins/ajnas because ajnas impart a suggestion of what melody is intended.

However, I am now of the opinion that phraseology and an understanding of the ajnas, and the modal identities that are present through the location (maqam) on the fingerboard is more significant to understanding and learning modal music, and discovering melody within that system.

To link certain notes along the “PATHWAY” of the fingerboard to certain “LOCATIONS” or modal identities is a better glimpse into the origin of this music.

While we search for metaphors to describe modal music, the best is the fretboard of a musical instrument on which the locations of modes (maqam) are placed.

You may start your “COURSE” (seyir) on a certain location (maqam) on the fretboard, and the maqams you pass by on your journey is a description of your seyir.

What we lost

We are slowly losing this way of describing Arabic music. This method is still used in Turkey, and in Iran, we have the “gushe” system immediately gives the educated musician a melody idea to work with.

Now we consider such maqams as Maqam Hijaz Kar Kurd as maqams, when they are probably best described as tarkib, compounds of two or more primary maqams. Thinking about the maqam as a particular combination and classifying it as such can help learners of modal music really grasp the modal phenomenon we encounter.

We also have a rich variety or what are called, transposed maqam. For example, the maqams Hijaz kar, Shad Araban, Suzidil, and Shahnaz. The basic ajnas (building blocks) of these maqams are the same, but start on different notes. Our Western music influence tells us that they are the same because the intervals are the same.

But this is misleading, because by starting on a different note, different qualities can emerge especially when playing an instrument like the Oud which resonates differently depending on the tuning of the open strings, and the abilities and limitations that certain finger positions offer.

Not only that, these transposed maqam have different seyir which can be described by their starting points on different notes, resting points, combinations with other modes, and finalis notes. By using the old system of maqam names associated with notes on the fingerboard, and more coherent picture can emerge. This is the true meaning of modal.

Start your journey learning Arabic Maqam with me.

Sign up for the OudforGuitarists newsletter.References:

Walter Feldman, Music of the Ottoman Court: Makam, Composition and the Early Ottoman Instrumental Repertoire (F. Noetzel, 1996).

Marcus, Scott Llyod Ph.D. Arab music in the modern period. Los Angeles: University of California, 1989.

This is very interesting content. Thanks for the information. Would it possible to add the references of tbe used sources (Feldman, etc.)?

I will add the full references.

very very interesting and enlightening aspect. i always found it so much more difficult to play modal music on the guitar in comparison to oud or sarod or whatever „eastern“ instrument. this blog gives me insight , why i experience this difficulty. too many options become a distraction, simply put. thank you very much , navid 🙏

You’re welcome Henrik.